By Evra Taylor

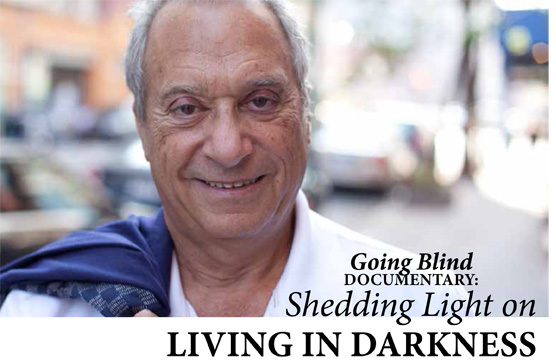

American filmmaker Joseph Lovett sits in front of a Humphrey Visual Field Analyzer and makes a searingly honest statement: “The prospect of going blind terrifies me. And my way of dealing with fear and terror is to confront it.” Lovett’s way of confronting blindness was to make the documentary Going Blind, a film tracking his vision loss and that of others.

American filmmaker Joseph Lovett sits in front of a Humphrey Visual Field Analyzer and makes a searingly honest statement: “The prospect of going blind terrifies me. And my way of dealing with fear and terror is to confront it.” Lovett’s way of confronting blindness was to make the documentary Going Blind, a film tracking his vision loss and that of others.

Lovett has been losing his vision to glaucoma – a condition he aptly describes as ‘a thief in the night’ – for over 20 years. When he realized that his doctors were not comfortable discussing sight loss with him, he started talking to others who had lost their sight. In the film, he profiles a number of people, including an Iraq War veteran and an art teacher whose near-total vision loss has forced her to discover alternate ways of expressing her art.

Acting as the film’s narrator, Lovett shows his subjects navigating the densely populated streets of Manhattan, where he lives, and delivers a cogent, almost dispassionate explanation of glaucoma and its workings: the function of the optic nerve, his diagnosis and vision loss, and its effect on his life.

Lovett says the film was intended for a broad audience, including sighted individuals, so they can better understand what life with vision loss is like, and physicians, so they will better understand their patients’ needs and concerns. Of course, Going Blind is also a film for people who have lost their vision, “so that they will become aware of all the help that is available to them in terms of training and new technology.”

People tend to grow up with a fear of blindness because we know so little about it, according to Lovett. “The fear turns into a prejudice against the blind. Sighted people tend to ignore blind people — they don’t talk to them, don’t engage with them and don’t learn about their lives. As a result, they remain ignorant of how people can lead totally regular lives but in a different way without sight. However, this can be turned around if you’re lucky enough to meet the incredible people I met while filming Going Blind. ”

Reaction to the film has far exceeded Lovett’s expectations. More than 200 organizations have purchased it and it has had multiple screenings by community groups, libraries and universities. (CNIB presented the official Canadian premiere of Going Blind in January 2011 at Toronto’s Scotiabank Theatre.) It is also being used for physician training and will air on U.S. public television in October 2012.

Said CNIB President and CEO John Rafferty: “It’s a great film that depicts both the emotional challenges and technical needs of someone learning to cope with vision loss. The film helps to show that – with the right support – it really is possible to see beyond vision loss, whether you’re a filmmaker, a war veteran, a teacher or anyone else”.

CNIB has described Going Blind as a film about hope beyond vision loss, even for people who, like Lovett, have made lives for themselves working in the visual world of television. In an interview with USA Today, Lovett recounted a visit to an art gallery that brought this realization into focus.

“I found myself in front of a very large canvas and looking at one aspect, one area of the canvas, that was very beautiful; (the paint was) very worked. I wouldn’t have noticed that detailing and wouldn’t have remarked on [the artist’s] craft and skill if my vision was working,” he said. “When you’re losing your vision and you’re paying attention, you begin to know what you don’t know and what you don’t see. You know that you should look deeper.”

Toward the end of the film’s preview, Lovett poignantly asks, “What will it be like to no longer be able to read a newspaper?” The preview concludes on a positive note with his statement, “What was once unthinkable is actually very doable, and it’s time for all of us to come out of the dark about vision loss”.

A preview of the film can be seen at www.goingblindmovie.com, along with Going Blind and Going Forward, the film’s Outreach Toolkit that shows step-by-step how an individual or organization can use the film to best serve their community. The Toolkit explains how to reach the largest number of people using media and news outlets to publicize a screening and draw an audience.

Going Blind was produced with major support from Pfizer Ophthalmics and The Readers Digest Partners for Sight Foundation.