By Paddy Kamen

Many players are vying for a piece of optical retail as the ownership and opportunity landscape continues to change.

In the past 20 years Canadians have seen huge changes in the overall retail landscape. Department stores that were once institutions, like Eaton’s, have disappeared, and The Bay (a.k.a. The Hudson’s Bay Company) with its iconographic Canadian symbols, is now U.S.-owned. Walmart dominates most communities of any size, while independent hardware, drug and bookstores are becoming a thing of the past. Chain stores dominate most sectors. Then there’s Internet shopping, with Amazon doing so well that they’re looking into creating drones to deliver parcels more efficiently than mail and courier services. It’s a brave new world, indeed.

Optical retail has not escaped these changes, although it is perhaps behind the trends rather than leading them. This article analyzes the current optical retail landscape and muses about the future. We ask: what types of ownership and partnership structures currently exist? Where is the growth? Are independents on their way out? How do consolidation and vertical integration affect other players? How will Internet retail shake out? And what does all this structural change mean for eyecare professionals, especially new graduates from opticianry and optometry programs?

Incumbents and New Players Vie for Market Share

What is driving the changes in optical retail? Margaret Osborne, acting chair of the School of Marketing and Advertising at Toronto’s Seneca College, says that two fundamental and opposing forces are occurring simultaneously. “Internally, ownership of the industry has consolidated considerably over the last 20 years. Vertically integrated incumbents with enormous market power now dominate the industry. The other major development is that new, external entrants are advancing. Here I include grocery retailers and mass merchandisers, as well as private equity firms who are attracted by the healthy profit margins (58 per cent, according to Statistics Canada) combined with the reality of an aging population. Today, only 65 per cent of eyewear sales originate in traditional optical goods stores and how long that will last is anyone’s guess.”

Incumbents Integrate and Consolidate

Vertical integration, whereby companies buy their suppliers or distributors, is very active within the industry. Luxottica and Essilor have been integrating for years. A newer entrant, FYidoctors, an optometrist-controlled chain, has its own lab and distribution and develops house brand frames.

Integration is not necessarily apparent to the consumer, but the fact that Luxottica owns

Integration is not necessarily apparent to the consumer, but the fact that Luxottica owns

LensCrafters, Pearl Vision andSunglass Hut, or that Essilor controls a majority of the optical labs in Canada may constrain opportunities for the traditional eyecare professional (ECP) owner-operated shop.

In 2013, the top four players (not necessarily retailers) accounted for approximately 44 per cent of total market share. The growth of the giants shows no sign of stopping anytime soon, and ongoing acquisitions and competitive activity will lead to increased concentration. According to an IBISWorld Industry report, the top four companies in the Canadian industry by market share are: Luxottica (20.4%), Sàfilo (17.3%), New Look Eyewear Inc. (4.6%), and Laurier Optical (1.5%)1.

However in optical retail alone, Alan Ulsifer, CEO of FYidoctors estimates that his company has approximately 12 per cent market share and that Iris2 has 10 percent. Ulsifer says that FYidoctors is second only to Luxottica and that, “We expect to be the leader soon.”

Consolidation refers to companies buying their competitors. For example, New Look recently purchased Vogue Optical and Greiche & Scaff, while FYidoctors purchased Vision Source in 2013.

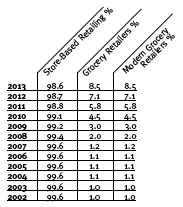

Grocery retailers are one example of external entrants advancing steadily into the optical sector. “Beginning with market share of two per cent in 2008, largely based on over-the-counter readers, they now hold 8.5 per cent and can be expected to achieve double digits in 2015,” notes Osborne.

Smaller Players Find Ways to Thrive

Smaller players are responding to industry integration and consolidation in various ways. One response is to band together; another is to fill a niche that still holds value for the owner and the public.

The banding together approach is exemplified by FYidoctors, a Calgary-based company that launched in 2007 with 13 optometrist-owned stores and now has 115 locations nation-wide.

Alan Ulsifer, CEO of FYidoctors, says there were two main drivers for the creation of the company: “We didn’t have the strength to compete with the larger chains in terms of our buying power. We also realized that the industry in the U.K. and U.S. was moving from an independent, medically driven model to a corporate box-store mentality. We saw an opportunity to bring together likeminded people and create a brand that pays attention to what the customer wants, while focusing on medical care and diagnostics. Consolidation in any industry is an opportunity to build value and create a strong brand and that was attractive to us, too.”

FYidoctors offers owners either a franchise option under the Vision Source banner or full membership under the FYidoctors brand. Under that brand, the company is buying up existing optometrist-owned retail locations at the rate of about two per month. Those who join the company may choose to acquire shares that give them a direct say in company decisions. There are opportunities for shareholders to participate through advisory committees and the board of directors. “No single person controls the company,” says Ulsifer. “No decision can be made to sell without two-thirds of shareholder approval.” Although FYidoctors is like a chain in many ways, the ownership model is more akin to a cooperative, according to Ulsifer.

The Vision Source arrangement is strictly a franchise wherein the owner pays a fee for services but remains independent. Vision Source retailers have access to FYi’s exclusive brands, as well as practice management solutions and access to group pricing discounts. “This gives us another model to appeal to more optometrists,” notes Ulsifer.

A different approach is seen in Opto-Réseau, a banner organization operating in Quebec since 1996. Executive Director Christine Breton (no relation to Envision magazine publisher Martine Breton) says the banner helps independent practitioners compete: “The industry has changed so much and everyone who wants to thrive needs the specialized services and structure that our group provides. Storeowners have to be up to date in terms of management, store design, business technology, optical equipment and consumer product. Owners need to know where they are going and how to get there. That’s where we come in.”

A different approach is seen in Opto-Réseau, a banner organization operating in Quebec since 1996. Executive Director Christine Breton (no relation to Envision magazine publisher Martine Breton) says the banner helps independent practitioners compete: “The industry has changed so much and everyone who wants to thrive needs the specialized services and structure that our group provides. Storeowners have to be up to date in terms of management, store design, business technology, optical equipment and consumer product. Owners need to know where they are going and how to get there. That’s where we come in.”

Those who join the group retain store ownership and may also become shareholders in Opto-Réseau. The original store name remains on the signage, with the Opto-Réseau logo beside it. “We make it easy for them to succeed by providing the infrastructure, right down to a monthly newsletter they can send out to their clients. And our buying power means they have more competitive pricing than they could achieve on their own,” says Breton. Banner members can participate on the administrative council and various committees. Opto-Réseau differs from a chain in that individual storeowners personalize their policies and procedures.

“We help them to grow in a strategic way and the profit stays with them. They pay us a monthly fee and this is probably the lowest fee in the market,” says Breton.

Another option for those who prefer to be completely independent is to join the Opto-Réseau buying group to take advantage of group pricing. Currently there are 95 stores in the buying group, including 69 Opto-Réseau banner stores.

Niche Strategy for Independents

Those who choose to start up as owner-operated independents, or who want to remain so, face considerable challenges. Margaret Osborne says that a differentiated strategy is essential to keep profit levels stable or, ideally, rising. High-end, artisanal frames may be a sound approach in this day of integration, consolidation and Internet marketing. Expenses for optical retail are increasing by an average of 7.2 per cent annually3, so while high-end niche independents may continue to do well, discount bricks-and-mortar shops are in a vulnerable position because the Internet channel is growing.

Internet Retail

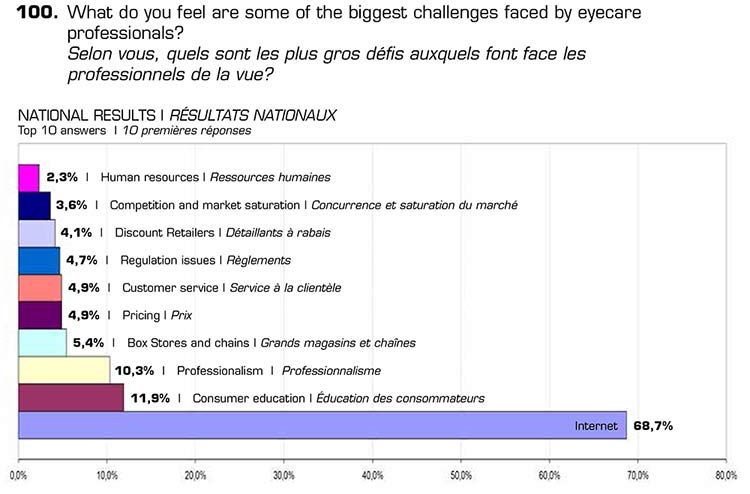

Internet retail presents both an opportunity and a threat to ECPs, according to the results of Breton Communications 2012 survey of the three Os. When asked to identify the greatest threat to their business, 68.7 per cent of respondents chose the Internet.

At the same time, the Internet was the most popular choice among those who specified where they think future opportunities in the industry will arise.

At the same time, the Internet was the most popular choice among those who specified where they think future opportunities in the industry will arise.

Internet retail sales still account for only a tiny portion of eyewear sales in Canada. The first year for which there are stats on this channel, 2008, shows a market share of 0.3 per cent, a figure that rose to 1.2 per cent in 2013 . Nevertheless Internet shopping is a growing trend4.

One of the most intriguing consolidation developments of 2014 was the purchase of Coastal Contacts by Essilor. Coastal had international sales of $196-million in fiscal 2012 5.

In an interview with Envision magazine, Essilor Canada President Marc Tersigni explained that the company is implementing changes in the way Coastal interacts with consumers. “Our goal is to have Coastal become more educative. The millennial shopper is the biggest wave coming, as boomers are retiring and spending less. This shopper is educated via the Internet, and Coastal will now be part of that, with a clear recommendation that consumers have their eyes and vision checked by professionals. The last thing on our mind is to devalue bricks-and-mortar. The Internet is a viable way to attract people to bricks-and-mortar and educate them. We see possibilities to create a stronger industry for all.”

In an interview with Envision magazine, Essilor Canada President Marc Tersigni explained that the company is implementing changes in the way Coastal interacts with consumers. “Our goal is to have Coastal become more educative. The millennial shopper is the biggest wave coming, as boomers are retiring and spending less. This shopper is educated via the Internet, and Coastal will now be part of that, with a clear recommendation that consumers have their eyes and vision checked by professionals. The last thing on our mind is to devalue bricks-and-mortar. The Internet is a viable way to attract people to bricks-and-mortar and educate them. We see possibilities to create a stronger industry for all.”

Tersigni envisions bricks-and-mortar locations using an Internet shopping channel to serve customers for whom the store-based product offerings are not sufficient. “I can see the first pair (being) purchased in the store, with the Internet channel used for the second or third pair and for sunwear,” he explains.

Tersigni has taken the step of introducing leaders in optometry and opticianry to Coastal’s management in order to create understanding and defuse potential points of conflict. He is also creating an advisory panel to help determine a path forward.

FYidoctors has also ventured into the Internet space with strategically branded product at competitive prices. They require active validation of the customer’s Rx, an approach which Ulsifer says addresses the concerns of professionals. “We won’t provide eyewear for children under 10 and we won’t do eyeglasses with prism. When a person places an order we will have an optician do PD and segment height virtually with specially developed software. Any complex prescription submitted will be followed up with a phone call.”

Will this Internet service be competing with FYidoctors stores? No, says Ulsifer: “The Internet service is more of an outlet concept, so the product on the site is very different than what is available in the stores.”

Opportunities for Eyecare Professionals?

As consolidation, integration and Internet sales channels continue to roll out, eyecare professionals of all kinds will be affected. Will there be fewer opportunities for them?

At the extreme end, Margaret Osborne sees few well-paid, full-time positions for opticians, as chains and independents alike focus on labour costs. “Market saturation could lead to some opticians being paid by the piece, while those with the best sales, service and skills will be employed across multiple channels. Sixty per cent of opticians are now working in traditional optical retail stores. We should be prepared for the landscape to be very different in 10 years.”

At the extreme end, Margaret Osborne sees few well-paid, full-time positions for opticians, as chains and independents alike focus on labour costs. “Market saturation could lead to some opticians being paid by the piece, while those with the best sales, service and skills will be employed across multiple channels. Sixty per cent of opticians are now working in traditional optical retail stores. We should be prepared for the landscape to be very different in 10 years.”

Osborne notes that the rate of new opticianry grads may contribute to the loss of viable full-time jobs because retailers look to labour costs as one place to eke out savings.

Alan Ulsifer likewise posits that there are too many optometry grads coming into the market. “The University of Waterloo created a bridging program to help grads from other countries upgrade, which is bringing in more than 40 extra grads a year. At the same time there are more qualified optometrists coming to Canada from the U.S. and it’s becoming easier to obtain a license to practice here. On top of that, older professionals are not retiring at the same rate.”

Optical retail is indeed a graying industry. Breton Communications 2012 survey found that 67.2 per cent of respondents were aged 40 or older and just 31.7 per cent were younger than 39. This reality makes many traditional ECP-owned optical shops potentially available to companies hungry to expand their market share.

“Increasingly frantic” is how Margaret Osborne describes the current cycle of acquisition and innovation by both incumbents and new players in the optical industry. “The dynamic and provocative nature of the tactics of the power players is creating pressure points for everyone. I contend that an industry shakeout is imminent. A new landscape will emerge in the next few years.”

- TURK, S. “IBISWorld Industry Report 44613 CA Eye Glasses & Contact Lens Stores in Canada.” IBISWorld Canada. IBISWorld Inc. December 2013. Web. 6 August 2014.

- Iris executives were unfortunately unavailable to be interviewed for this story to the sad and untimely passing of their founder Francis Jean.

- Optical Goods Stores (NAICS 44613): Retail Revenues and Expenses.” Industry Canada. Government of Canada. 15 July 2014. Web. 6 August 2014.

- « Eyewear in Canada. » Euromonitor International. December 2013. n.p. Passport GMID. Web. 6 August 2014.

- SHAW, H. “Online Retailers Turn Back to Bricks and Mortar to Boost Sales.” Financial Post. National Post, 11 March 2013. Web. 6 August 2014.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Types of Optical Retailers

Let’s be clear about what each term means as we analyze optical retail trends.

Chains: A group of more than four retail outlets owned by one firm/individual typically operating under the same name. Chain stores usually have similar interior design, operating policies and products. E.g. Hakim Optical, Iris, New Look Eyewear. Many department stores are chains.

Banners: This can be a confusing term. ‘Banner’ refers to a type of branding with a specific name, appearance and policies. For example, Loblaws owns several banners, or brands, including Superstore and Zehrs. Luxottica operates under different banners (LensCrafters, Pearl Vision) with LensCrafters corporately owned and Pearl Vision operating as franchises. However, the term is also sometimes used to mean an independently owned practice that is affiliated with a chain or central office. The owner pays fees for the right to use the banner (brand) and to participate in centralized buying, marketing, professional programs, etc. Owner autonomy varies greatly depending on the banner. E.g. Opto-Réseau.

Franchises: A franchise is a business where the owner (franchisor) sells the rights to the business’ name, logo and model to a third party operator (franchisee). Franchise agreements can differ, but often the franchisee has limited control over product selection, suppliers, store design, layout, location etc. E.g. Iris (some stores), Pearl Vision.

Cooperatives: Employee (or provider) owned corporations that act like a chain but are owned by many versus one individual. These companies have more complicated governance structures to ensure all shareholders have a voice. E.g. FYidoctors

Independents: Practices that are owner-operated by an eyecare professional. According to Statistics Canada, independents operate three or fewer stores, while more than three constitute a chain.

Mass Retailers and Department Stores: These stores sell a variety of goods and may have an optical department within the store. E.g. Costco and Walmart.

Supermarkets: Increasingly, large supermarkets are diversifying beyond food and beverage products into clothing, appliances, housewares, electronics and optical goods.